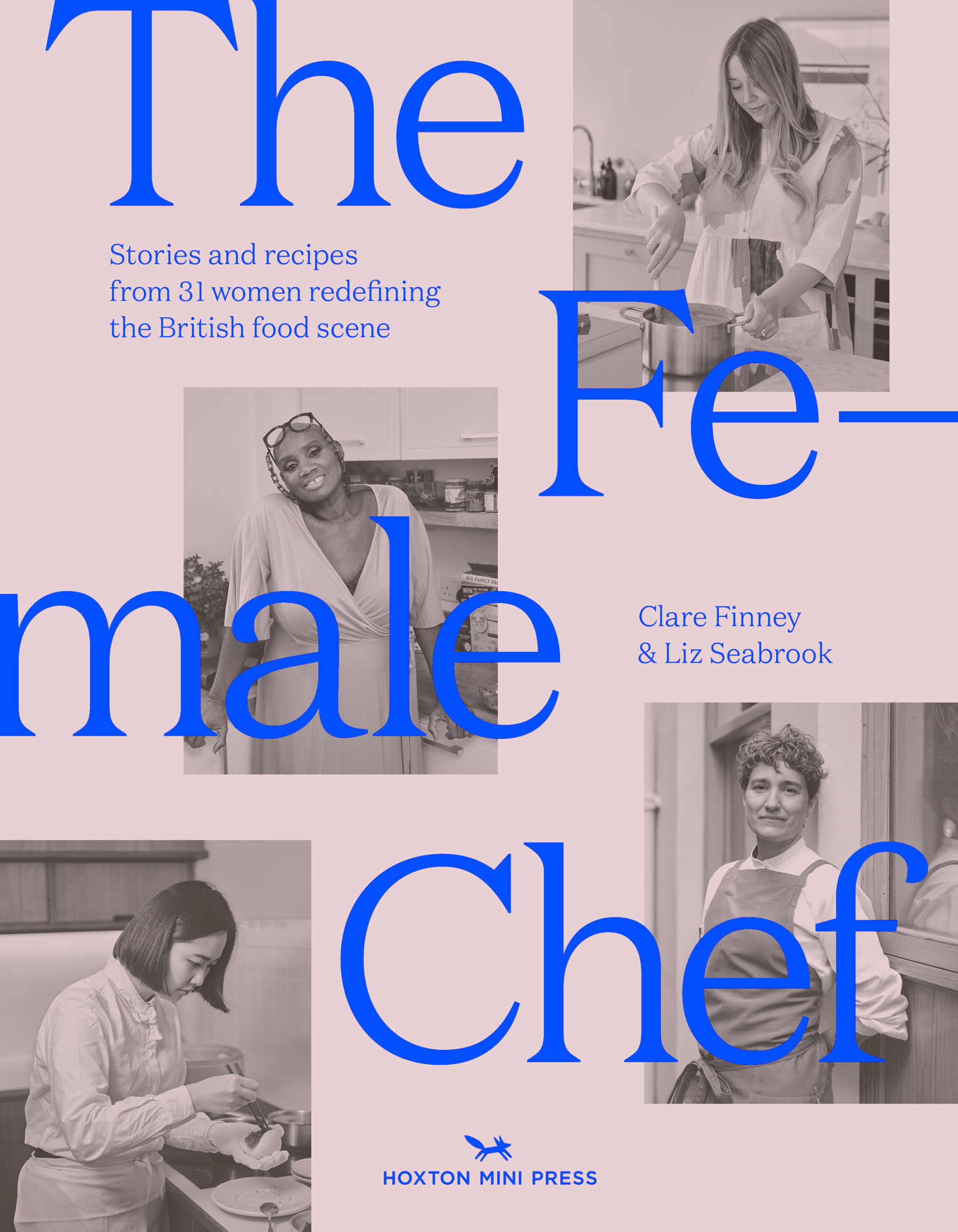

The Female Chef: At The Table with Clare Finney

To mark International Women’s Day, we knew exactly who we wanted to chat to — Clare Finney. Clare’s book, The Female Chef, came out towards the end of 2021, and was perhaps one of the most important cookbooks to have been released last year. It sets out to explore the nuanced relationship between women and food, featuring interviews with and recipes from Ixta Belfrage, Pamela Yung, Julie Lin, Anna Jones, Asma Khan, Ravneet Gill and others. We spoke to Clare about where the idea for the book came from, the process of creating it and how women are breaking down the gendered distinction between the terms ‘cook’ and ‘chef’.

Tell us a little bit about where the idea for The Female Chef came from.

The concept was initially devised by Hoxton Mini Press, who approached me with the idea of doing a book on female chefs in early March 2020. They were interested to know whether I could treat the idea in such a way that rendered it relevant and necessary – whether that was even possible to do.

“Though the rarefied world of gastronomy has always been male dominated, the foundation – the heart – of food as sustenance has historically and biologically been a female preoccupation.”

After all, the very term ‘female chef’ itself runs the risk of being reductive – we don’t refer to ‘male chefs’, do we – and any treatment of ‘women and X profession’ needs to be considered, nuanced, and well-justified. Yet the more I mulled it over – with my mum, a career woman, feminist and inspiration, and my grandma, herself a female chef of sorts – the more I was struck by the uniqueness of the relationship between women and food, as distinct from women and say, architecture, science, banking or law.

In these professions, women have historically been almost entirely excluded. Only in the past 50-odd years have women come in and shaped them. In the case of food, however – well, women have been there all along. They have been simultaneously been in the kitchen all day every day, and yet excluded from the kitchens of fine dining establishments. They have cooked and baked – even butchered and filleted – but they have not been chefs, bakers, butchers or fishmongers. Though the rarefied world of gastronomy has always been male dominated, the foundation – the heart – of food as sustenance has historically and biologically been a female preoccupation.

In this, the world of food represents a complex, protean exception to those other previously male dominated professions, where the public narrative around gender has extended toward casting it off entirely – for it is almost impossible to draw any clear lines between food and gender; between feeding and femininity. Now that the sands are shifting and food as ‘industry’ is moving from something male-lead to something more balanced, the question of whether/to what extent female industry leaders feel they should encompass womanhood within their professional life – indeed cherish it as a fundamental source of their success – or follow their counterparts in banking, law, science and so on seemed more relevant than ever.

Where did the process of writing the book begin — how did you select which women you spoke to and how to navigate the topics you wanted to chat to them about?

I had to whittle a list of 50 to 60 chefs down. It goes without saying it could have been longer. In the end, I applied what I thought was a simple metric: a woman who had cooked or was currently cooking in a restaurant kitchen, and who was making a concerted effort to shake up the industry – either by what they cooked, how they cooked, how they ran their kitchen or, as was the case with many of these chefs, all three. I wanted to talk about how they came to their current careers; their training, champions and challenges; and where they felt they sat on the chef/cook spectrum. I was also keen to address the intersectionality of women’s experience in the food world, and to not draw any hard and fast rules.

There are so many nuances in the terms ‘cook’ and ‘chef’, and you talk about it in such a beautiful way in the book — can you tell us a little bit about the distinction and how it’s relevant to women in food?

Chatting to my grandmother, a former hotel owner, about the proposal, I found out that she used to refer to her female kitchen staff as cooks and the men as chefs, though they had the same role in the kitchen. Of all the many angles through which I thought I could approach this subject, the one that stood out most is this invariably gendered distinction we make between ‘cooks’ and ‘chefs’, and the way in which cheffing was changing thanks to women entering the industry.

Linguists will at this point be reaching for the dictionary, yet the Oxford English Dictionary is hardly cut and dried about the distinction. It states that a chef is ‘a person whose job is to cook, especially the most senior person in a restaurant, hotel, etc’; a cook is ‘a person who prepares and cooks food, especially as a job or in a specified way’. There is no mention of the popular assumption that chefs cook professionally, and cooks cook in the home; nor of the way interpretations vary according to where you are in the world; nor of the gendered associations the words have gathered like moss over the years.

It’s been a fascinating lens – all the better for yielding quite unexpected results. Some ‘chefs’ were rejecting the term in favour of ‘cook’ or ‘leader’. Others were setting out to redefine it, even feminise it, making it more holistic and inclusive. I won’t go any further than that – it’s all in the book! – but suffice to say it’s been an extraordinary journey, and more expansive and inspiring than I ever imagined.

In the introduction you write, “Where once the division between dining out and dining in seemed absolute, now the boundaries feel increasingly blurred.” We definitely agree, but we’d love to know how you’ve noticed this change and what role have female chefs played in this?

The advent of supper clubs, pop-ups, street food stalls and – more recently – finish-at-home dining boxes have made restaurants out of people’s homes; residencies, takeovers and collaborations have seen so-called cooks brought into restaurant kitchens. Female chefs have been at the forefront of many of these developments, particularly supper clubs, which enabled talented women to commercialise cooking at home, and without necessarily being professionally trained. Rosa’s Thai Cafe (Saiphin Moore) was born out of a street food stall; Asma Kahn’s restaurant and ensuing success was born of a supper club; Ravinder Bhogal’s of pop ups; Zoe’s Ghana Kitchen was born of a combination thereof.

You worked with Liz Seabrook on the photography for the book, travelling around to various chefs homes. What did it feel like going into and documenting the domestic kitchens of some of the UK’s most fantastic chefs? How did that compare to the experience you might have had in their restaurants, if different at all?

Sadly, on account of Covid, Liz got far more of an insight into these chefs lives and kitchens than I did. Most of my conversations were carried out on Zoom, Teams or a phone call, in the end! That said, I rarely sensed any clear delineation between chefs’ work and their home. The two seemed to meld together; a bit of their heritage, a bit of what they’d been taught, a bit of what they’d picked up from friends, all forged in the fires of their considerable creativity. Tellingly. many of the chefs spoke of their staff as being like family, so this clearly also had implications for their culture.

What more can we be doing to promote gender equality within the food industry? How can we support female chefs and contribute towards changing the traditionally macho and masculine world of the restaurant kitchen

It’s a huge question, and the answer is both very simple and very complex. I can’t pretend to have the answers but, for a start, we need more women in the kitchen. As I write in the introduction, Escoffier’s brigadier approach to running a kitchen is inevitably, inherently white, male and Western. To challenge it, we need women from a variety of ages, cultures and backgrounds, and we need them in leadership positions. Only by having women present, representing the interests and needs of and looking out for other women can the culture start to change.

Of course we have to ask, which are your favourite recipes within the book and why?

Such a tough one! My personal favourite is Anna Jones’ sweet potato dal, because it’s so comforting, nourishing and doable. But then my friend made Pam Yung’s mozzarella in carrozza the other day – one of the book’s more time consuming dishes – and it blew my mind. I also have a special place in my heart for Sabrina Gidda’s gnudi; I’d never tried gnudi prior to meeting Sabrina seven or eight years ago in a restaurant she used to work in, called Bernadis. I couldn’t believe anything could be so deeply satisfying, yet so light and pillowy . What’s so lovely about this book is that the recipes are so varied, and so uniquely expressive of the chef who chose them. Everyone I know to have cooked from the book has alighted on something different.

Clare Finney’s Pantry

(5 items that are always in your pantry, or that you can’t live without!)

1. Belazu tahini

2. Good anchovies

3. Embarrassing basic olives

4. Manilife peanut butter

5. Wholegrain mustard

Read more: The Female Chef

An in depth exploration of the relationship between women and food, and simultaneously a celebration of some of the UK’s most talented chefs — the game-changers and the women shaking things up — Clare’s book The Female Chef is one for your kitchen counter and your bedside table. Published by Hoxton Mini Press, 2021.